At the beginning of his research, his novel approach to digitalization had already made him a Forbes 30 Under 30 pick. Now, two years on, he and his colleagues can see how they can help patients, and are already working out how to expand the technology to other hospitals.

Why the liver? Prague's IKEM (Institute of Clinical and Experimental Medicine) is the largest superspecialised facility in the Czech Republic, focusing on treating cardiovascular disease, organ transplantation and the treatment of metabolic disorders in people from all over the country. In all of this, the liver is more complicated than other organs.

An overly complex organ

"When you do a CT scan or use other imaging methods, the heart, for example, is nice to look at, it's well characterized. This is not the case with the liver. They have a lot of structures, hepatic veins, arteries, and therefore patients are still given a contrast agent to show the different layers. But this results in several hundred images, and a physician has to scroll through a huge amount of data, which is not efficient," says David Sibřina, who, surprisingly, is not a physician. He did all his undergraduate studies, including his PhD, in the UK, where he focused on 3D graphics, computational medicine and virtual reality. Today he is a specialist in medical data visualization. And that's what attracted him to IKEM.

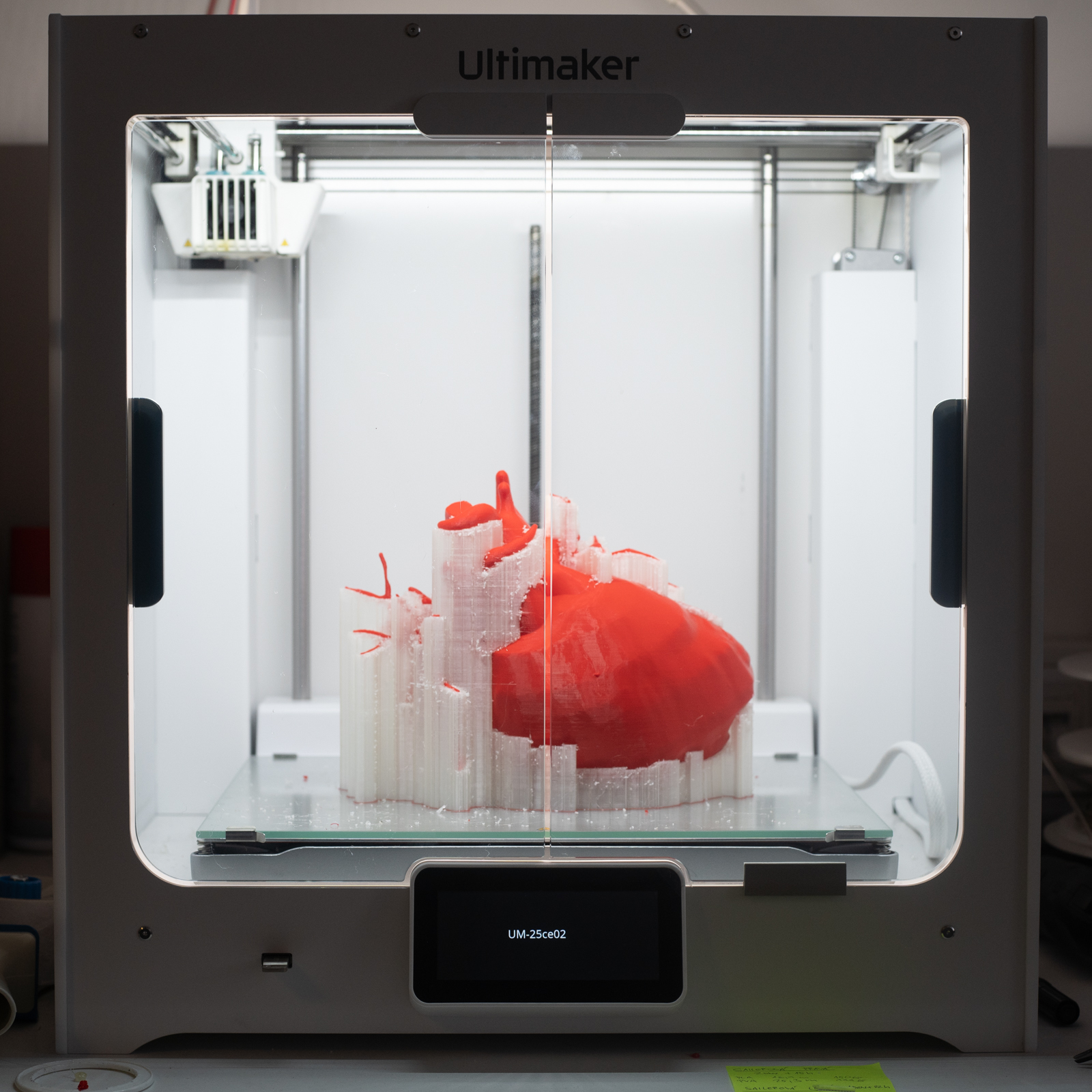

It had already become apparent that MRI data, for example, is sometimes not well understood by surgeons and is very difficult to understand without the assistance of the trained eye of a radiologist. "Later, therefore, we started to work with 3D printed models, but they are relatively expensive and also take a long time to acquire, which we cannot afford for urgent cases. However, the models had the advantage that one has a haptic response with them, they make it easier to plan. So the idea of bringing all this into virtual reality was born," says the man who became a researcher at the hospital in September 2020. 3D printing is still used today, but virtual reality tools have their place mainly in the most complex cases, such as donating part of a liver from a living donor.

IKEM surgeons typically deal with liver transplants from living and deceased donors, or the removal of a part of the liver that has been attacked by a disease. During the donation process, doctors compare data from the organ donor (the size of the liver and its structure) and data about the recipient's body (such as the size and characteristics of the abdominal cavity) to see if one and the other will be a good match. And it is for this, and planning the subsequent surgery, that the tools that the technology team has programmed, operates and feeds data to are used.

Surgeons who want to learn

"I was in the right place at the right time. In fact, the surgeons themselves felt that they wanted to solve the problem of surgery planning, so they are all the more keen to learn how to work with the new tools," says Sibrina. In 2024, they deployed the virtual reality system for more than 487 indicative procedures. The data shows that it has had positive benefits not only in more efficient planning of surgical procedures, but also in better "matching" of organ donors and recipients.

"Previously, individual donor and recipient parameters were compared, such as biometrics, height, weight, gender or how big the abdominal cavity was. But it turned out that this may have disadvantaged smaller women, men and adolescents, for example. Indeed, it may have seemed impossible to place the organ. Now we have accurate, personalized models and all the waiting patients on the registry are photographed, so this eliminates doubt and means better chances for patients," Sibřina points out.

.jpg)

The team she leads within IKEM is unique not only in the Czech Republic, but also globally. The big advantage is that the hospital itself has created its own technology workplace, so the IT specialists are close to the patients, to practical medicine. Commercial companies are also trying to develop on a large scale, but they are running up against the fact that they do not have patients.

The bottom line is that the tools are there, the evidence of their functionality is there, so the technology should ideally be spreading now. Sibřina and his colleagues are waiting for a peer-reviewed paper to be published, and at the same time, they are eying the idea that they can help other hospitals. But they need them to set up their own technology centers, because specific hospitals should manage their specific data.

Further progress will depend on how quickly the things that go with it all develop. The spread of technology will depend on its integration into standard medical practice and on the ability to effectively link innovation to clinical practice. The development of headsets is another matter – doctors would need them to shrink into the form of conventional dioptric glasses. And those in charge of development would again like to see complementary elements used in the development process. While mobile phones are now developed for Android or iOS, there are many times more platforms here, so it is difficult to overcome the fact that the different devices do not understand each other.